Z2A - Unpacking Custom Sample - Part 1

Today, we’re going to analyze the first custom malware sample in Zero2Automated course !

Triage

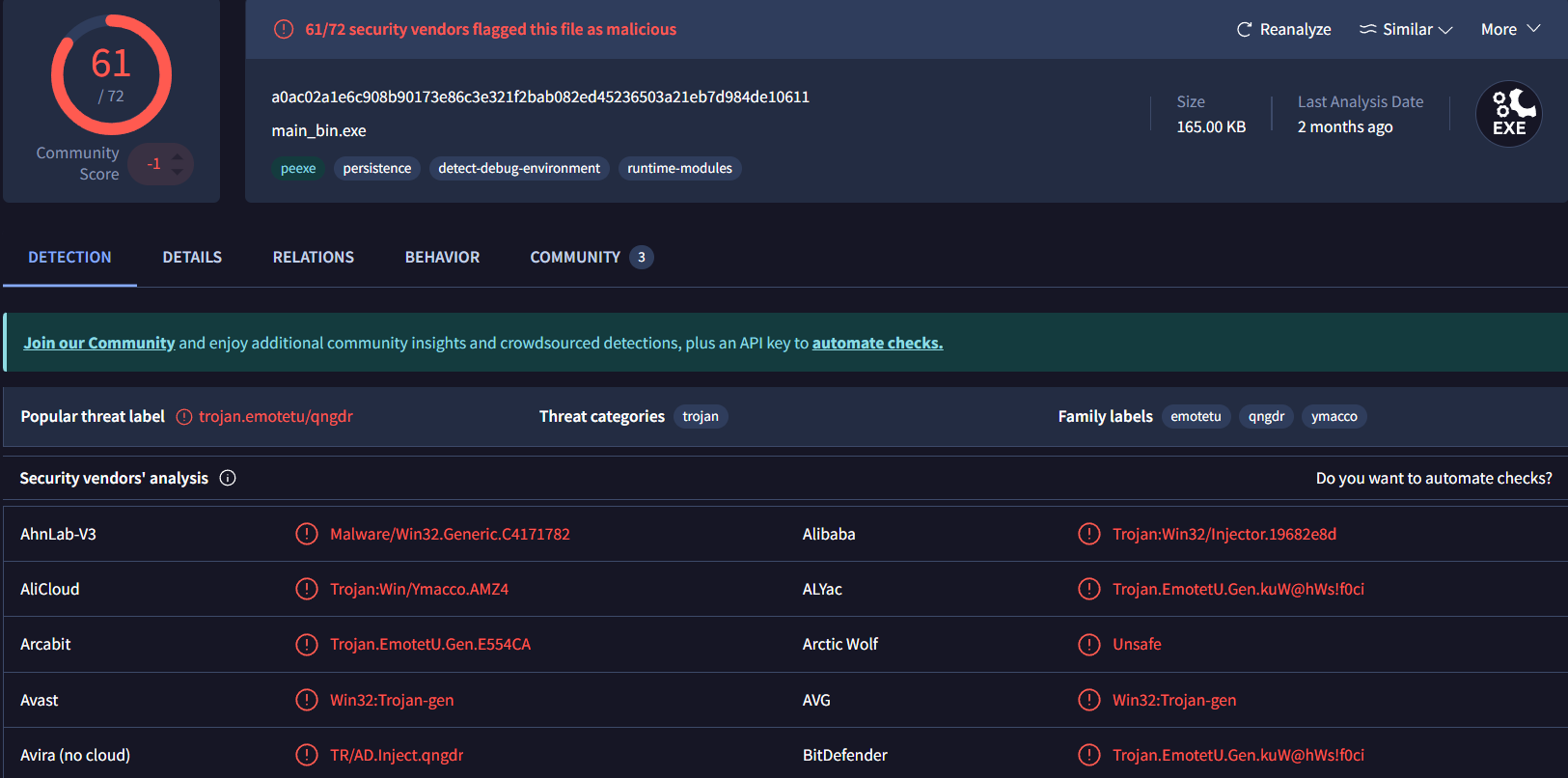

| SHA256 | a0ac02a1e6c908b90173e86c3e321f2bab082ed45236503a21eb7d984de10611 |

|---|---|

| Score VT | 61/72 |

Basic Binary Information

The first step after

Triageof the binary, is to perform a basic static analysis. The goal ? Make assumptions about the information that are available directly in the structure of the sample.

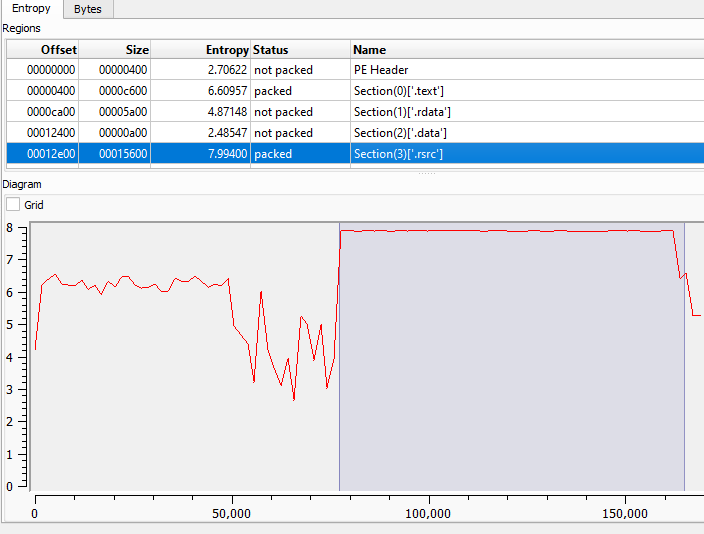

Using Detect It Easy, it appears that the .rsrc section has a constant high entropy. This indicates an encrypted zone inside the resource and surely a packed malware.

DetectItEasy screenshot - .rsrc section entropy diagram Another indicator supporting our hypothesis is the presence of a single imported library named

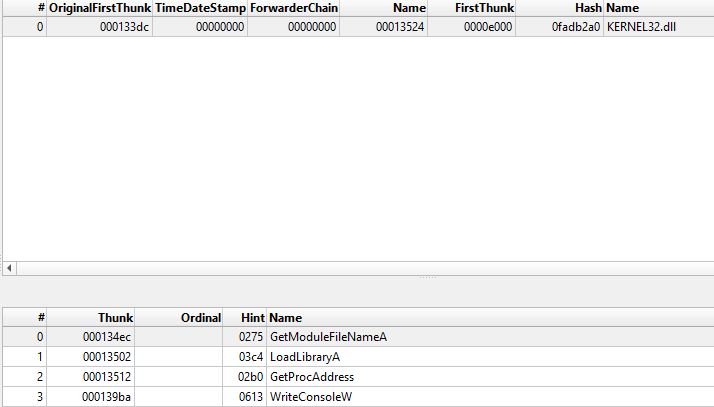

DetectItEasy screenshot - .rsrc section entropy diagram Another indicator supporting our hypothesis is the presence of a single imported library named KERNEL32.dll.

This is a technique aimed at concealing the capabilities of the malware and exposing them while running.

It is very likely that the sample dynamically resolves further APIs by calling LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress (two API present inside Kernel32.dll).

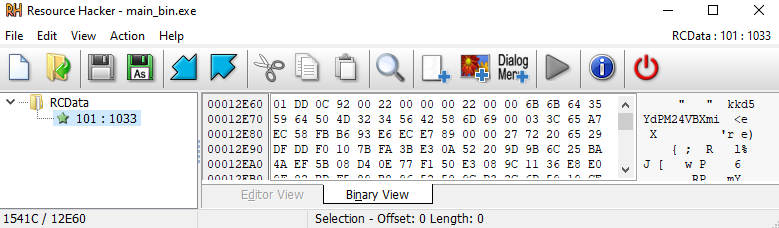

PE-Bear - Only Kernel32.dll Library Using Resource Hacker, we found an RCData Resource represented with integer

PE-Bear - Only Kernel32.dll Library Using Resource Hacker, we found an RCData Resource represented with integer 101.

Resource Hacker - strange resource Finally, several strings appeared to be obfuscated or encrypted, preventing an analyst to find clues about the purpose of the malware.

Resource Hacker - strange resource Finally, several strings appeared to be obfuscated or encrypted, preventing an analyst to find clues about the purpose of the malware.

Dive into assembly code

(Keep in mind that in the screen, several strings are already deobfuscated due to my early work with IDA Free).

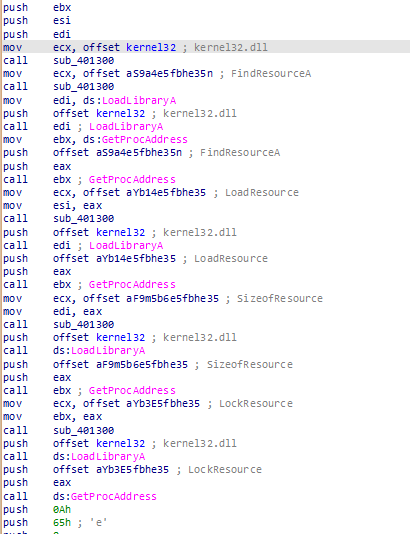

The first lines of code contains multiple offset containing obfuscated strings. Theses strings are then used with LoadLibraryA and GetprocAddress to dynamically resolves API function. Looking at the screen below, each push <offset> is followed by a call to the previously mentioned API.

Resolving of the WinAPIs Following the offsets into

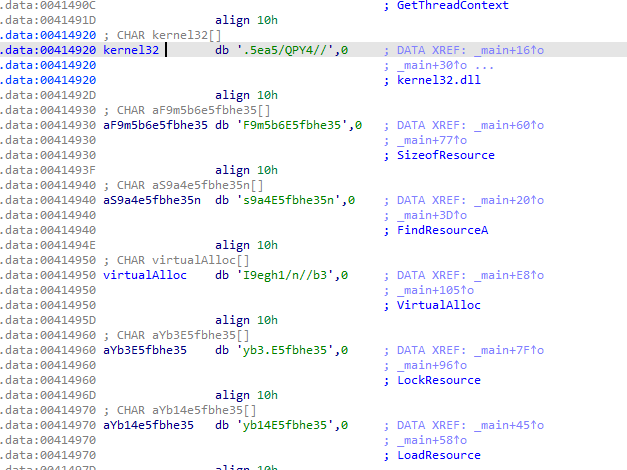

Resolving of the WinAPIs Following the offsets into .data section shows us the list of obfuscated strings :

.data - encoded strings The strings are decoded using the

.data - encoded strings The strings are decoded using the sub_401300 function. We found a base64 format string "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ01234567890./=" and a rotation number of 13 that clearly indicates a ROT13. ROT13 and Base64 are sometimes used together for obfuscation purposes.

To easily decode all the strings and continue our analysis, we can the python script below. The script fetches the .data section and uses a regex rule that match any character whose ASCII code is between 32 (space) and 126 (tilde).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

import pefile

import re

def find_strings_zone(data):

result = []

pattern = rb"[ -~]{8,}"

for match in re.finditer(pattern, data):

result.append(match.group().decode('ascii', errors='ignore'))

print(result)

return result

def retrieve_strings(filename):

pe = pefile.PE(filename)

data_section = None

for section in pe.sections:

if b".data" in section.Name:

data_section = section.get_data()

break

return find_strings_zone(data_section)

strings = retrieve_strings(r"C:\<X>\main_bin.exe")

format = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ01234567890./="

final_string = ""

for input_string in strings:

for x in input_string:

indexOfChar = format.find(x)

if (indexOfChar + 13 < len(format)):

result = indexOfChar + 13

else:

result = indexOfChar - len(format) + 13

final_string += format[result]

print(input_string + " : " + final_string )

final_string = ""

Output :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

F5gG8e514pbag5kg : SetThreadContext

.5ea5/QPY4// : kernel32.dll

pe51g5Ceb35ffn : CreateProcessA

I9egh1/n//b3rk : VirtualAllocEx

E5fh=5G8e514 : ResumeThread

Je9g5Ceb35ffz5=bel : WriteProcessMemory

I9egh1/n//b3 : VirtualAlloc

E514Ceb35ffz5=bel : ReadProcessMemory

t5gG8e514pbag5kg : GetThreadContext

.5ea5/QPY4// : kernel32.dll

F9m5b6E5fbhe35 : SizeofResource

s9a4E5fbhe35n : FindResourceA

I9egh1/n//b3 : VirtualAlloc

yb3.E5fbhe35 : LockResource

yb14E5fbhe35 : LoadResource

With the decoded strings, we can already deduct what’s the next steps of this first stage malware. We notice a lot of Resource and Memory API.

FindResourceA, LoadResource and LockResource are used to retrieve a pointer to the first bytes of the encrypted resource (remember our previous step ? When we found that .rsrc section has a strangely high entropy :) )

This post is aimed to understand precisely how this malware works, we will looking at all the steps.

After the malware retrieved every pointer of the APIs it needed, FindRessourceA is used to get a handle to the specified resource’s information block.

1

2

3

4

5

6

ressource_handle = ((int (__stdcall *)(_DWORD, int, int))findRessource)(0, 101, 10);

/* HRSRC FindResourceA(

[in, optional] HMODULE hModule, -> 0 : current process

[in] LPCSTR lpName, -> 101 : ID of the resource

[in] LPCSTR lpType -> 10(RT_RCDATA) : Application-defined resource (raw data).

);*/

Then, LoadRessource is called to load the resource into memory and get a handle that can be used to retrieve a pointer on the first bytes of .rsrc with LockResource.

1

2

3

first_bytes_handle = ((int (__stdcall *)(_DWORD, int))loadResource)(0, ressource_handle);

ressource_size = ((int (__stdcall *)(_DWORD, int))sizeOfResource)(0, ressource_handle);

rsrc_first_bytes = ((int (__stdcall *)(int))lockResource)(first_bytes_handle);

Next, the .rsrc is ridden to retrieve the size of the encrypted part in the section. Indeed, the first bytes contains useful information for decryption.

1

size_encrypted_data = 10 * *(_DWORD *)(rsrc_first_bytes + 8);

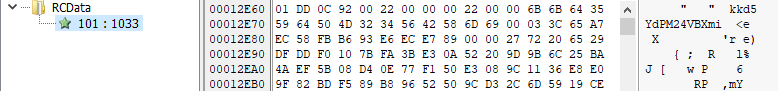

When inspecting the binary with Resource Hacker, we discovered an RCData resource named 101, with a total size of 0x1541C bytes.

Resource Hacker - RCData resource Looking back at the code, we can see that it reads a DWORD (a 4-byte integer) located 8 bytes after the beginning of this resource. The value recovered there is

Resource Hacker - RCData resource Looking back at the code, we can see that it reads a DWORD (a 4-byte integer) located 8 bytes after the beginning of this resource. The value recovered there is 0x2200.

Next, this value is multiplied by 0x10 (16 in decimal), giving us 0x15400. This seems to represent the expected size of the decrypted data.

Now, if we compare this with the actual resource size:

1

2

3

0x1541C (resource size)

- 0x15400 (expected size)

= 0x1C

The result likely corresponds to a header or metadata in this case, it appears to mark the first bytes of the encrypted data.

The malware then uses VirtualAlloc to allocate memory for the encrypted data. The function returns a handle to the newly allocated region, stored in handle_alloc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

handle_alloc = ((int (__stdcall *)(_DWORD, signed int, int, int))ptr_virtualAlloc)(0, size_encrypted_data, 4096, 4);

/*LPVOID VirtualAlloc(

[in, optional] LPVOID lpAddress, -> 0 : current process

[in] SIZE_T dwSize,

[in] DWORD flAllocationType, -> 4096(MEM_COMMIT)

[in] DWORD flProtect -> 4(PAGE_READWRITE)

);*/

Once the memory is allocated, the function sub_402DB0 is called to copy the encrypted data **from the resource into this newly allocated region:

1

sub_402DB0(handle_alloc, rsrc_first_bytes + 0x1C, size_encrypted_data);

This copies 0x15400 bytes (starting 0x1C bytes after the resource’s beginning) into the allocated buffer.

Next, the malware resets a structure called unk_data by filling it with zeros, similar to how memset() works:

1

2

key = 0;

sub_4025B0((__m128i *)unk_data, 0, 0x102u);

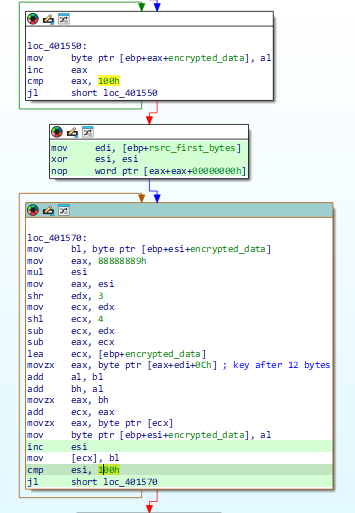

This step is likely part of the decryption setup of RC4 Algorithm. Indeed, we can observed successive block looped 0x100 (256) times. See another post for RC4 encryption details

In IDA Free - RC4 Behavior The decryption key is stored inside

In IDA Free - RC4 Behavior The decryption key is stored inside .rsrc starting 12 bytes from the resource head.

1

key += v18 + *(_BYTE *)(index % 0xFu + rsrc_first_bytes + 12);

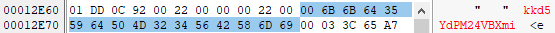

The disassembly indexes this area with index % 0xFu, which implies a 15-byte key. Inside, Resource Hacker, we observed the decryption key which, I admit, was very obvious : "kkd5YdPM24VBXmi"

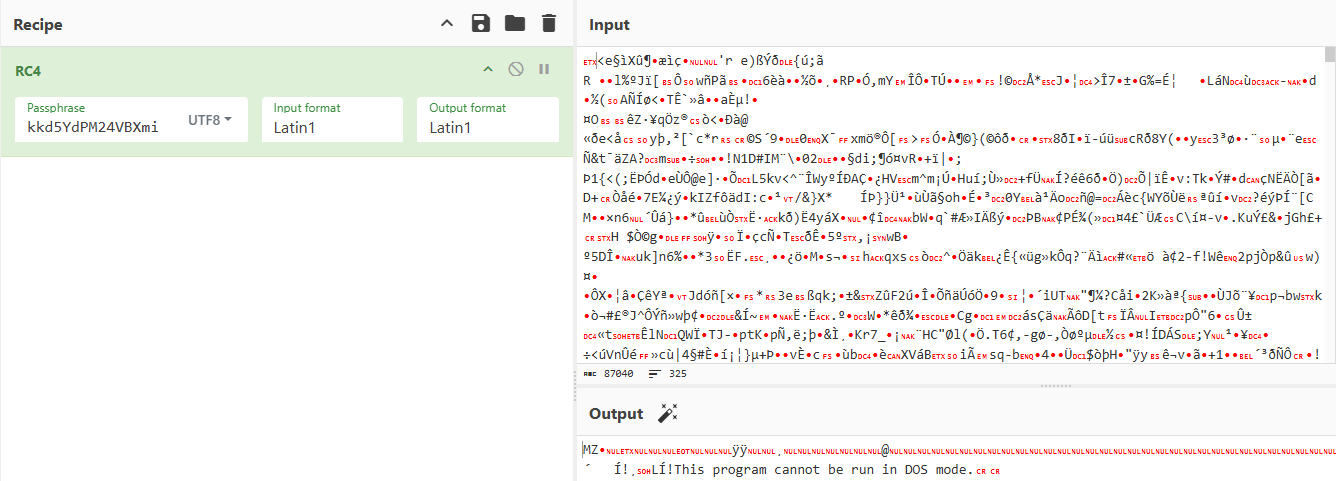

Decryption Key Before writing a script to automate the decryption of the section, we can confirm this hypothesis with Cyber Chef by extracting after

Decryption Key Before writing a script to automate the decryption of the section, we can confirm this hypothesis with Cyber Chef by extracting after rsrc_first_bytes + 0x1C.

CyberChef - Decrypted MZ File Wow ! A PE file is hidden !

CyberChef - Decrypted MZ File Wow ! A PE file is hidden !

This freshly decrypted PE file is then sent to an injection function.

1

2

mov ecx, [ebp+lockRessource] # lockRessource : Pointer to the decrypted data

call injection_process

Injection of the second stage

Before analyze this second stage, we need to understand how this executable is injected inside another process like we saw earlier in our Basic Dynamical Analyze.

The prototype of the function indicates that decrypted data is view as a array of DWORD.

1

2

3

int __thiscall injection_process(_DWORD *dword_pefile) {

...

}

The decompiler uses a _DWORD * view of the file, so indexing is by 4 bytes. The offset of the value retrieved is 15 * 4 = 60 (0x3C) → IMAGE_DOS_HEADER.e_lfanew. This offset is well known because it corresponds to e_lfanew a pointer to the PE Header.

The function confirm the presence of the signature 0X4550.

1

2

3

4

5

ptr_e_lfanew = (_DWORD *)((char *)dword_pefile + dword_pefile[15]);

if ( *ptr_e_lfanew != 0x4550 ) {

return 1;

}

v28 = 0LL;

In addition, this function creates a suspended process. The dwCreationFlags is set to 0x00000004 (CREATE_SUSPENDED)and does not run until ResumeThread API is called.

Also, a 4 bytes zone is allocated inside the own process with flAllocationType set to 0x00001000 (MEM_COMMIT). A _CONTEXT structure is retrieved into handle_alloc and a ContextFlags is set to 0x10007 - CONTEXT_FULL.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

if ( !API_CreateProcessA(Filename, 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 0, (LPSTARTUPINFOA)v29,&lpProcessInformation) {

return 1;

}

/* ... */

handle_alloc = (_CONTEXT *)API_VirtualAlloc)(0, 4, 4096, 4);

handle_alloc->ContextFlags = 0x10007;

Then, the context of the suspended thread is stored inside handle_alloc.

The use of ReadProcessMemory on the suspended thread indicates that a value is put inside v27.

Using ReadProcessMemory, the value at Ebx + 8 in the suspended thread is written inside v27. The register EBX points to the PEB (Process Environment Block). In addition, in the 32-bit PEB structure, the field ImageBaseAddress is at offset 0x08. http://blog.rewolf.pl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/PEB_Evolution.pdf

1

2

3

4

5

if ( !API_GetThreadContext)(lpProcessInformation.hThread, handle_alloc) ) {

return 1;

}

/ * ... */

((void (__stdcall *))API_ReadProcessMemory)(lpProcessInformation.hProcess, handle_alloc->Ebx + 8, v27, 4, 0);

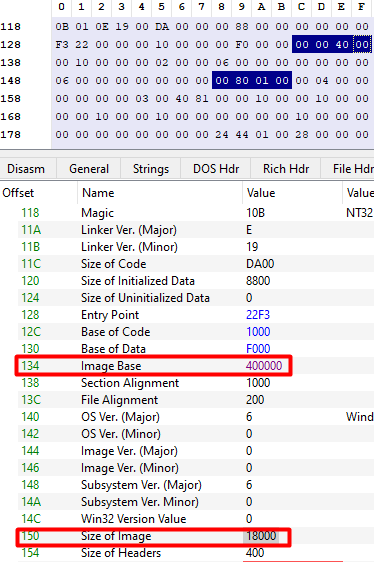

A new region of memory is allocated inside the thread. The function uses different value stored inside the FILE_HEADER - 0x100 like Image Base & Size Of Image. Keep in mind the offset stored inside e_lfanew and the DWORD view of the file (cf. comments below).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

allocated_memory = ((int (__stdcall *))VirtualAllocEx)(

v28,

ptr_e_lfanew[0xD], // (0xD * 4) + 100 = 0x134 Image Base

ptr_e_lfanew[0x14],// (0x14 * 4) + 100 = 0x150 Size Of Image

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE

);

Both values can be observed inside PE-BEAR.

PE-Bear - ImageBase / SizeOfImage After creating the remote image, the injector first writes the PE headers and then iterates the section table to write each section into the allocated memory.

PE-Bear - ImageBase / SizeOfImage After creating the remote image, the injector first writes the PE headers and then iterates the section table to write each section into the allocated memory.

In the snippet below it writes only the SizeOfHeaders bytes (the value read from the Optional Header):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

((void (__stdcall *))API_WriteProcessMemory)(

v28, // hProcess

allocated_memory, // lpBaseAddress

dword_pefile, //lpBuffer

ptr_e_lfanew[0x15], // (0x15 * 4) + 100 = 0x154 Size Of Headers

0

);

The code below loop on each section using the Sections Count that can be retrieved with [cp_ptr_e_lfanew + 3] -> [100 + (3 * 2)] = pefile[106].

For each iteration, WriteProcessMemory is called and 3 values are collected:

base + *e_lfanew + (0x41 + i * 0xA) * 4=RVAbase + *e_lfanew + (0x43 + i * 0xA) * 4=Pointer to Raw Database + *e_lfanew + (0x42 + i * 0xA) * 4=Size of Raw Data

Where

iis the index of the current section

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

if ( *((_WORD *)cp_ptr_e_lfanew + 3) )

{

offset_section = 0;

do

{

((void (__stdcall *))API_WriteProcessMemory)(

v28, // hProcess

allocated_memory + *(_DWORD *)((char *)&dword_pefile[offset_section + 0x41] + dword_pefile[0xF]),

(char *)dword_pefile + *(_DWORD *)((char *)&dword_pefile[offset_section + 0x43] + dword_pefile[0xF]),

*(_DWORD *)((char *)&dword_pefile[offset_section + 0x42] + dword_pefile[0xF]),

0);

++index_section;

offset_section += 0xA;

}

while ( index_section < *((unsigned __int16 *)cp_ptr_e_lfanew + 3) );

}

As discussed earlier, the image base of the suspended process is overwritten with the image base of the current process:

1

2

3

4

5

6

((void (__stdcall *))API_WriteProcessMemory)(

lpProcessInformation,

handle_alloc->Ebx + 8,

image_base,

4,

0);

Next, the EAX register of the suspended process is updated with the Address of Entry Point (*e_lfanew + 0xA * 4 = 0x128). Once this modification is made, the thread context is updated accordingly.

Finally, the execution of the thread is resumed by calling ResumeThread:

1

2

3

handle_alloc->Eax = v23 + cp_ptr_e_lfanew[0xA];

((void (__stdcall *))setThreadContext)(DWORD1(v28), handle_alloc);

((void (__stdcall *))ResumeThread)(DWORD1(v28));

This concludes the first part of our analysis of this sample.

In the next part, we’ll dig into the decrypted MZ payload and explore its real purpose and behavior.

Is it another layer of obfuscation? A fully functional second-stage malware? A loader for something even more interesting? We’ll find out.

See you in the next article ———————

R3dy